Mixing the old to give birth to the new. With the development of new technology, art materials have become more accessible and thus easier to reproduce. But to what extent is one allowed to own them?

In 1919, when Marcel Duchamp parodied Leonardo’s Mona Lisa and used it as a base for L.H.O.O.Q., it became one of his best-known pieces of art. Duchamp drew a moustache and beard on a cheap postcard reproduction of the picture. He also appended the title directly under his realisation. The name of the piece is a pun: pronounced one by one in French it sounds like “Elle a chaud au cul”, “She is hot in the arse” in English. It is a vulgar expression that connotes a woman’s sexual eagerness. Beyond the literal meaning of the phrase, it could also refer to the fact that the Mona Lisa (and its various reproductions) have been exposed so much to the public gaze that her status is challenged as an art object. Duchamp called it a “rectified ready–made” and he considered his addition a correction of an already existing product. He used the reproduction of a masterpiece from the history of painting just as he would have used any other mundane/utilitarian object. But can he really claim a picture as his own after only adding a moustache? Can an artist claim that the assembly of pre-existing works of art is a new creation of his own?

Nowadays, new forms of art and thus new kinds of artists are raising this issue once again. They have continued to create new forms of appropriation and have made this a new art movement on its own. Let’s look at two examples:

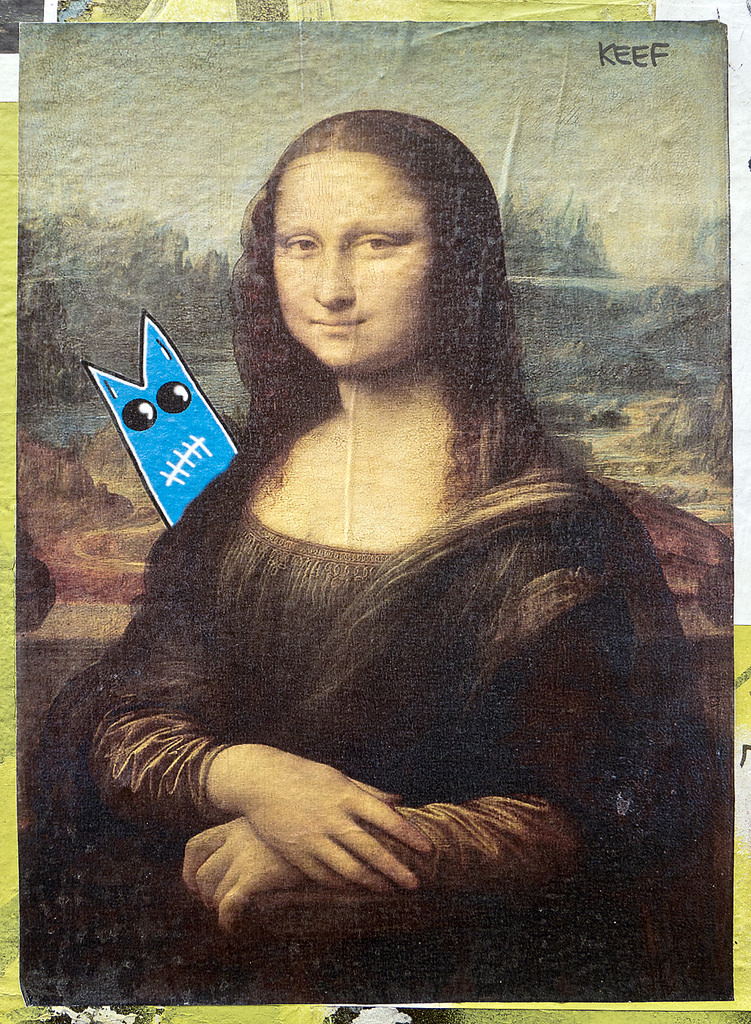

While wandering in the streets of Paris, London, and many other cities around the world -or even just on the Internet-, you might have come across the work of KEEF (@sadkeef on Instagram). KEEF is a recognizable figure, a very simplistic and colourful rabbit-like character, and the street artist’s trademark. He appears in various forms of street art from graffiti to collage and stencil. As is the case for the vast majority of street artists, it is almost impossible to gather information about his creator apart from work he shares on various social media and displays in the streets. One of the series consists in adding this original character to already existing material like the map of the London Tube or a home-printed version of classical paintings (such as The Wave by Hokusai and The Birth of Venus by Botticelli ). But the artist signs the name of the character on top, just like Duchamp before him, he changes the original signature. The artist makes these classical pieces of art his own by adding a piece of original art. Can it be the beginning of appropriation as a new form of art in itself?

In KEEF’s works, the borrowed elements are clearly visible, but sometimes the differentiation between the original and creative part is far less visible. In Sea and Spar Between, Nick Montfort and Stephanie Strickland worked on a coded piece of digital poetry. Nick Montfort describes the two artists’ work on his blog as a generator that produces a navigable space of stanzas and draws from the vocabulary and their combined reading of Emily Dickinson and Herman Melville. This generative work thus creates poetic lines mixing words and expressions from two sources of classic American literature: Melville’s Moby Dick and Dickinson’s poetry.

But at first sight, the reader can possibly mistake these poems for original ones written by Monfort and Strickland alone. Indeed, the work presents itself to the viewer as a vast ocean blue page crowded with trillions (225 to be precise) of stanzas. Anyone visiting the site can randomly navigate through them by moving the mouse, choosing specific coordinates or use other tools to manipulate the page as explained in the instruction guide proposed on the website. The real creation does not primarily reside in the visible poetry as in the Python code, which recombines the texts for the automatic formation of lines and stanzas. Monfort and Strickland clearly explain the code in the section of the site dedicated to the code which is easily accessible. Nick Montfort also adds in the licence of the code that anyone can copy or make use of it in some other way to create another project. As the creative coding part is freely accessible and reusable by anyone, Monfort and Stickland inject their own work of art into the cycle of appropriation and reusable art.

To some extent, this could be a matter of perception. Pieces that appear as original depend on the audience’s ability to recognize the remixed version of already existing material. Appropriation is revealed by the audience’s personal culture. But one can reflect on the nature of the original version that is reused. Then there are the often discussed matters of copyright, whether or not the original material is still recognized as a piece of art or if it slowly became a disposable image/text/material in the public domain. In the two examples above, the literary and pictorial works of art entered the public domain a long time ago. It means that there is no copyright attached to it. They can be reused for free, without the need to ask for permission. In fact, ironically, as new adaptations of a public domain work, they are protected by copyright laws. Nevertheless, for KEEF’s work, even if the artworks themselves are in the public domain, the photographs that he uses might not be.

To some extent, this could be a matter of perception. Pieces that appear as original depend on the audience’s ability to recognize the remixed version of already existing material. Appropriation is revealed by the audience’s personal culture. But one can reflect on the nature of the original version that is reused. Then there are the often discussed matters of copyright, whether or not the original material is still recognized as a piece of art or if it slowly became a disposable image/text/material in the public domain. In the two examples above, the literary and pictorial works of art entered the public domain a long time ago. It means that there is no copyright attached to it. They can be reused for free, without the need to ask for permission. In fact, ironically, as new adaptations of a public domain work, they are protected by copyright laws. Nevertheless, for KEEF’s work, even if the artworks themselves are in the public domain, the photographs that he uses might not be.

The over-sharing of culture that results from the ever-growing presence of the Internet and social media usage, might accelerate the transformation of unique works of art into new bits of a globally shared database.

Barbara Fasseur